The Missing Arabatchi

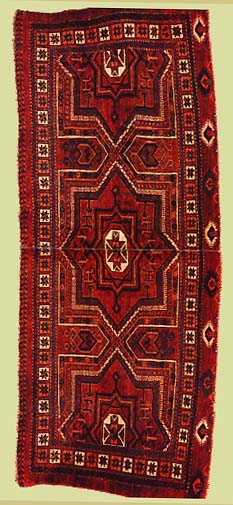

One day Peter Saunders was visiting and I showed him two pictures. One picture was of plate #171 in Oriental Rugs from Pacific Collections. This is a large powerful white field Kazak rug with three medallions dated to circa 1700. The other picture was of an Arabatchi torba, turned 90 degrees to level. After a brief introduction to Central Asian history I will return to our conversation about the relationship between these two weavings. One must bear in mind that the Arabatchi torba might be little more than 100 years old while the Kazak rug might be 300 years old.

Throughout Central Asian history we have learned that many Turkic speaking tribes’ people, Turkomen, were driven from their lands and nomadic style of life into subsistent existence in cities. The city herein referred to might be little more than a collection of mud brick dwellings, a jail, an administrative office, etc.

The Osmanli clan of the Chodor were driven out of Turkistan by the Mongols. Afterwards their skills in horse mounted warfare helped their descendants rule Turkey for hundreds of years as the Ottoman. Their eventual assimilation was so complete they no longer exist as a separate ethnic identity. Something very similar to this had already happened in Egypt where the horse mounted Turkic speaking warriors’ descendants became the Mamuluk Empire. Another of the major tribes of the Oguz confederation, the Arabatchi, virtually disappeared except for a small group of people cited by Moshkova and others.

Where did the Arabatchi go? Many of them left the tribe and drifted into the polyglot of Turkic peoples of the Caucasus. The Mongol had a word for those people and clans who left the authority of the hoard… Kazak. So to look for the lost Arabatchi we seek evidence of their weaving in the Kazak weavings of the late 17th century Caucasus.

First I want to show why the Arabatchi left Khiva. The Turkomen hoard, mainly the Salor and the Tekke, were driven from the Mangeshak peninsula in the late 17th century by a severe and protracted drought.(1) The true nomadic Turkoman is no friend to any city dweller. The Turkoman were predatory toward city dwellers, most of the time. The Salor arrived in Khiva in force around 1800 AD. The Tekke followed them. Both tribes were hardened by existence in a too harsh environment and in a very foul mood having lost many grandmothers and small children.

Just imagine you are a city dweller in Khiva around 1690 AD. You have your cute silk robe on with a couple of nice daggers in your belt when off on the horizon a growing cloud of dust heralds the arrival of a large group of people, The Hells Angels.

Khiva was closer to the Turkoman nomads than any other city on Earth. Khiva was a walled city and I can assure you they quickly closed their gates. I suspect that the Arabatchi had been at Khiva for a long time. They really have no iconographic connection to the other tribes in terms of their weavings. They were the only tribe to use a main carpet gull on their chuvals. Chuvals were very important dowry items. When used they were visible at long range and indicated tribal identity at long range. All the other Turkoman tribes, including even the Chodor early on, used the chuval gull for their chuvals. This habit of using the chuval gull on all Turkoman chuvals showed their common and larger incorporation into the great blood lines of the Oguz Turkomen, their “spiritual” ancestors.

I think the Arabatchi headed for the hills, the Caucasus mountains, so to speak ahead of the arrival of the full body of Turkoman refuges. I am quite sure the Arabatchi Khan and his family were eventually retained as “permanent guests” by their Salor masters at Khiva. The Salor and Tekke ruled Khiva for about fifty years. There is a pair of Arabatchi chuvals in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art that date to the early 18th century; in my opinion. See plate #54 in Turkmen by Mackie and Thompson. The characteristics of early 18th century Turkoman weavings, specifically those from Khiva, have only recently been recognized. This period represents the high point for Turkoman weaving. They had excellent water and pasture. The dyes they produced in this period are unequalled in my experience. The wool of fantastic quality. I once owned a now famous mid 17th century Tekke chuval and still own an early 18th century Tekke torba. The dyes and wool of the early 18th century piece are better by far than the mid 17th century piece. See Hali #55, Ghereh # 17, or Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies 5, for a picture of the mid 17th century Tekke chuval.

Now back to my conversation with Peter Saunders. I told Peter what I have briefly outlined above. He was initially shocked. I assume he was shocked at the idea that anybody might have an original idea about the subject. He said that this was the best idea about carpets that I have ever had. Then he sort of sneered, you would have to know Peter to understand this, and said it was all brilliant but 180 degrees out of focus.

Peter said, “what you have actually discovered is the true inspiration for this particular genre of Arabatchi torbas. In other words Peter thinks the design migrated from the Kazak main carpet to the Arabatchi torba. I think the historical evidence suggests the population was moving in the opposite direction, from Khiva Westward towards the Eastern Caucasus Mountains. There is no reason to suppose this movement was only in this direction. Many Turkomen certainly went Eastward towards Mongolia and China. The Salor and the Tekke were under some considerable pressure from the Qalmuqs, located to the North of the Mangeshak peninsula, during the 17th century. Dzhikiev recorded a legend stating that the Chodor also defeated the Salor during the 17th century. The Qalmuqs and the Chodor could be said to have run the Salor out of the Mangeshak peninsula to Khiva in Khorazem.(2) I theorize that the displaced Salor and Tekke displaced the older more settled Arabatchi towards the Eastern Caucasus Mountains.

There I believe the Arabatchi settled among the indigenous Kazak population where their older torba designs became the inspiration for a brand new and very successful main carpet design for the Kazak people. As evidence of this fact I draw your attention to a rug found in “Oriental Rugs From Pacific Collections” plate # 171. My point is easiest made in direct comparison with details from this very old Kazak and from the Arabatchi torba, that can be seen in Mackie & Thompson, plate # 55.

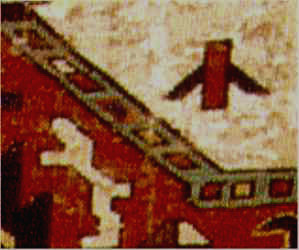

Notice in the pair of pictures above that if indeed this is a degenerative Arabatchi design we should see vestigial clues as to the origin of design. Please note the hook which appears to be a meaningless addition in the Kazak is a degenerated form of the Arabatchi double hook to the right. Also note how the circles of the outer border of the Arabatchi star become the colored squares of the Kazak. The two headed animal? in the Arabatchi torba has degenerated into a kind of floral leaf form in the Kazak. In fact every design motif in the field of this Kazak rug echos a well known Turkoman design. I see along the sides of the white ground field of the Kazak two designs in particular that are intimately associated with Turkoman design, the kochank and the arched form from the Arabatchi torba we are examining. The Kazak does have a pair of samovar’s in its’ field. Not every design found in the Kazak can be traced back to the Arabatchi torba but the overall design layout along with the fact that essentially every design found on the Arabatchi is found reintrepreted in the Kazak indicates to me that the Arabatchi torba was the inspiration for the Kazak. This idea is supported by the fact that this genre of Kazak design appears to have been degenerating ever since its’ brilliant beginning.

The simple devices found at the vertical extremes of the eight pointed stars on the Arabatchi torba are found simplified in two similar devices on the 17th century Kazak rug.

Could an Arabatchi torba design traveling to the Eastern Caucasus have been expanded and rotated to fit the looms of Kazak weavings to become one of the four main and most beloved Kazak designs from then till today? Looking at the Kazak rug we’ve been making our comparisons with I’m struck by the primitive vitality and power of this Kazak weaving! The movement of the weaving’s themselves is all that’s really necessary in this process but the interpretation of the original design and the attention to detail that a displaced Arabatchi weaver would bring to this process could make the design translation much more efficient and aesthetic. I think a good analogy would be a native musician whose music is taken to a new set of instruments. The music must be “translated” from one key to another. Without the original artist to make criticisms concerning this translation the music might easily be destroyed in the process. In other words to produce a masterpiece like this Kazak weaving from the expansion and rotation of an original Arabatchi torba would require the presence of an Arabatchi weaver capable of creating the original. The point I have been trying to make regarding the relationship of an old Arabatchi torba design to the design of an early 18th century Kazak rug is impossible to prove. What seems obvious to me might seem totally unconvincing to another connoisseur, like Peter Saunders who came to the opposite conclusion.

(1) Vanishing Jewels, pp 32.

(2) ibid. pp.32; footnote 38.