Introduction

This subject would have seemed illegitimate just a few years ago because rug weaving wasn’t thought of as a significant Armenian enterprise throughout most of the 20th century. Even today some rug enthusiasts feel that Armenian rugs are only those inscribed with Armenian writing. It has largely been through the work of the Armenian Rug Society and its members that we are now coming to terms with the important role Armenians have played in rug culture and more specifically in Caucasian rug weaving through the ages.

The current category of collectable Armenian rugs is mainly composed of rugs inscribed with Armenian writing and dates. This trend in Armenian rug connoisseurship deflects world attention away from the larger impact Armenian weavers had on Caucasus Mountain weaving and design.

With this paper I am suggesting a new genre of collectable Armenian rugs, those incorporating minimalist crosses into their designs. A minimalist Christian cross is one that is elongated by a single additional knot towards the weaving’s bottom (origin), metaphorically towards the Earth, like the true cross. Many such weavings were the products of Armenian weavers and need to be identified, cataloged, and preserved.

Caucasian rugs are some of the most aesthetically fertilized on earth; neither overbearing nor pretentious, Caucasian rug designs are simple yet psychologically profound. The contribution of Armenian artisans through the centuries to the great reservoir of Caucasian Rug designs only recently is becoming adequately appreciated.

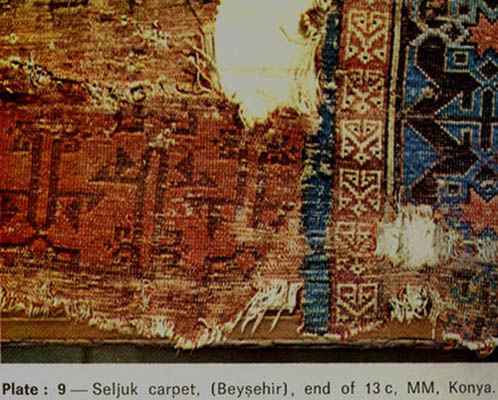

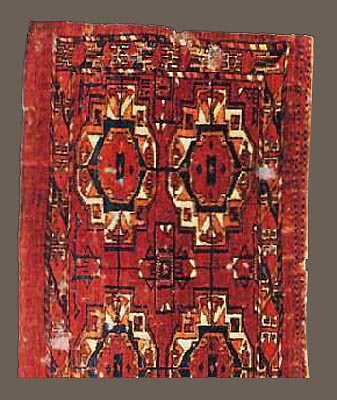

Armenia is situated in a strategic location serving as a major conduit between Asia and Europe. Through the centuries the Armenian material culture has been influenced by many great empires. Armenia served as a melting pot for ancient mythologies along with their associated designs. These designs included, among others, the great dragon of ancient China.

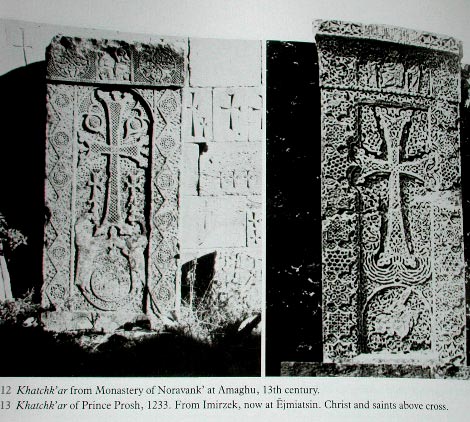

The Armenian Nation is credited with being the first official state in history to embrace Christianity as its’ national religion. This fact is significant considering that Armenia is and was surrounded on all sides by Moslem neighbors. In fact Armenia has churches dating back sixteen hundred years and this fact is of considerable importance to my thesis. The church must be strongly considered as a source for Armenian rug symbolism and aesthetics. The church must be looked at from the outside in and the inside out for associations with rug designs. The last part of this paper deals with a specific example of how such an analysis can work to explain a rug’s design.

Part 1

The international patronage for Caucasian rugs with Armenian writing has made such carpets virtually disappear from the world’s market places. One rarely encounters a nineteenth century inscribed Armenian rug for sale anymore. It is definitely time to expand the definition of Armenian rugs to include those weavings that have symbolic, technical, or geographical associations with Armenia or expatriated Armenians.

I see a symbolic association between some Caucasian weavings containing small Christian crosses worked skillfully into their designs and an Armenian provenance. I believe that in some areas of rug production, Karabagh for instance, Armenian weavers frequently identified their Christian faith and thus their Armenian identity with tiny Christian crosses.

Also, often included are stars, animals and human figures.

What Christian symbol could be better suited for this purpose than the cross? In this context there are a large number of Caucasian examples with small six knot crosses, still only the weaver’s intentions make these crosses significant. One cannot say that all Karabagh rugs with six knot crosses are Armenian but one can suspect that most of them were.

The cross also has many pagan associations stemming from before the time of Christ, and even afterwards, so the significance of tiny crosses in Caucasian rugs also depends on their historical, ethnographic, and geographic contexts. The cross is also a natural elaboration or step forward in the evolution of weaving design. The cross might not necessarily represent anything more than a simple design so only the weaver’s intentions ultimately determine the significance of crosses.

The identification of some rugs with Christian crosses as the work of Armenians is suggested, in part, by population statistics. One can be more confident about such associations when a given rug can be related to a specific geographical region based on its technical weave characteristics.

Murray Eiland recently published the demographic data for the later 19th century Caucasus Mountains in the book, “Passages: Inscribed Armenian Rugs”. Murray’s data shows that there were far more Armenians in the Karabagh region in the later 19th century than any other group.

The way tiny crosses are included within the body of a weaving can also provide hints or clues regarding the weaver’s intentions beyond simple statistics and geography.

Here is a white ground Shirvan area prayer rug that seems to offer a vital clue.

Included in this rug’s design is a small intricate motif worked discretely into a side margin of the field that represents a woman with a Christian cross associated with her head. The weaver seemingly portrayed herself wearing a dress, an apron, and a scarf. By connecting a tiny cross to her head, I believe this weaver was asserting that the cross represented her as a Christian.

The weaver of this fine Marasali prayer rug wanted the world to know that an Armenian girl created it. Bear in mind this rug is dated 1312 or 1896 so this weaver must have been fully aware of the atrocities being committed against Ottoman Armenians and possibly against her own family. I am here referring to the Hamidian massacres of 1895-96. This small symbolic signature possibly represents an act of rebellion by the Armenian girl who wove it into this fine carpet. If many Caucasian weavings with minimalist Christian crosses worked thoughtfully into their designs are the work of Armenian weavers, then some of these pieces may be the most interesting of all Armenian rugs to collect.

Part 2

Armenian family weavers, traveling north out of Ottoman Armenia in the second half of the 19th century, were leaving home to work under the watchful eyes of Islamic employers who had little tolerance for Christianity.

It was solely Armenian cultural virtues and weaving skills that allowed these weavers to go northward into Caucasus Mountain villages and find work. In this way they earned the hard currency so needed by their families back home. This fact seems so obvious yet some rug enthusiasts still don’t believe that Armenians generally wove rugs. The fact is Armenians were some of the very best rug weavers in many Caucasus Mountain villages.

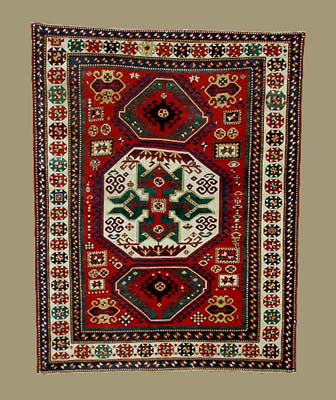

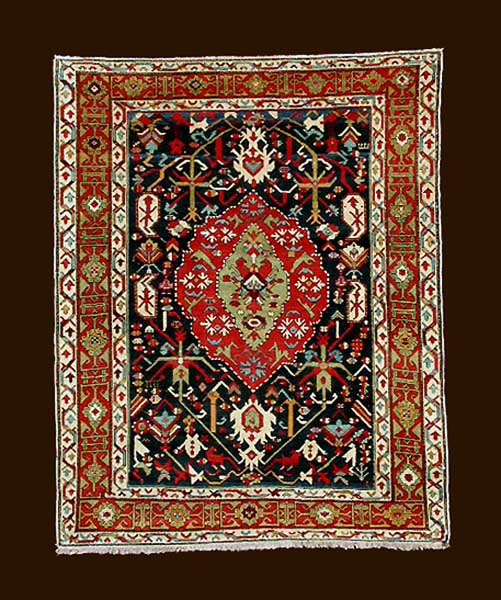

During better times, towards the middle third of the 19th century, weaving of extremely high quality was carried out in the Caucasus Mountains and especially in old Armenia. Lori Pambak was one Armenian city that produced very high quality rugs.

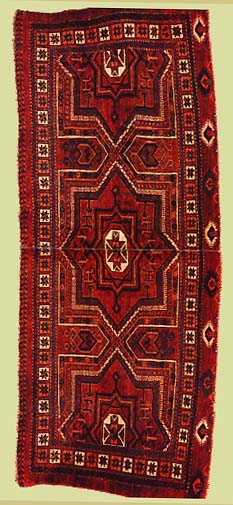

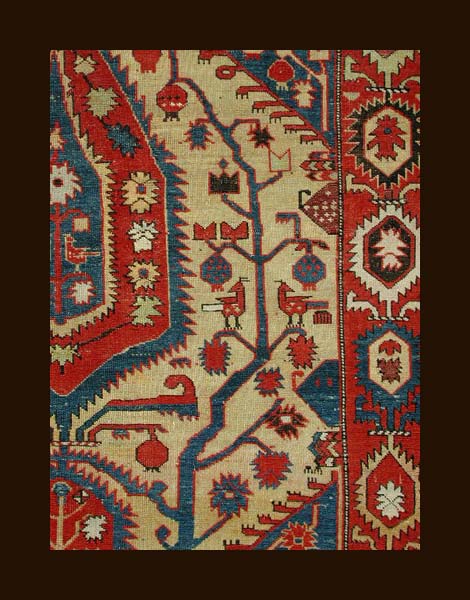

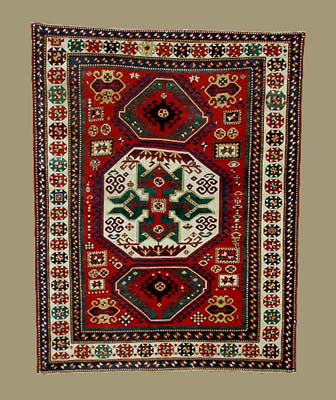

Certainly the best weavings from Lori Pambak, prior to about 1880, are some of the most sought after in the world. The Lori, seen in the picture below, is a good example of this type of rug.

In this Lori Pambak rug Christian crosses are discreetly introduced into the major border at one end. These unobtrusive Christian crosses ‘push’ the central star upward from its central position. Was the weaver trying to indicate some equivalence between the Cross and a star in heaven? Surely this spatially orchestrated interplay between cross and star was intentional. The weaver may have been making a small statement, to those sensitive to its content, in order to communicate that these tiny crosses, associated with a heavenly star, represented Christ. I believe such intentionality indicates the weaver was a Christian Armenian and in this way the rug was surely signed.

Expatriated Armenian weavers generally wove at least one rug for their own dowry and they used the best materials they could afford for these special often inscribed rugs.

Caucasian rugs from the Karabagh region include those from Karabakh, (Karabagh, Artsakh, and Ngorno-Karabahk). These rugs were largely woven by Armenians in the later 19th century; so rugs from this area with tiny Christian crosses are likely to be Armenian rugs.

In a few weaving centers north of Karabagh, like Shirvan and Kuba, workshops existed producing high quality weaving using the very best dyes along with top quality wool. Weaving centers like these employed some Armenian weavers and some of their rugs also include tiny Christian crosses. The Marasali introduced earlier is a fine example of this type. The flowers at the bottom of its field are rendered in pure silk dyed with cochineal.

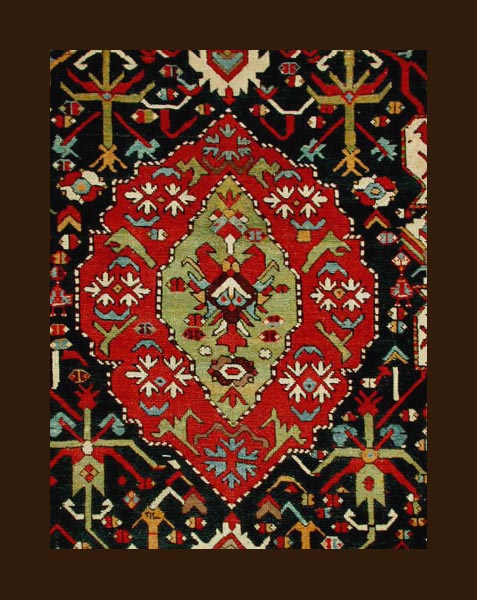

Some older rugs with a shirvan type weave also show crosses in their compositions.

Here is an example dated 1815 that I believe is an Armenian rug that has crosses used in its composition. Included with the many 5 five knot crosses is one 6 knot cross that is associated with a small motif that ‘rises’ above the central medallion via an old weavers trick, that of letting one edge of the motif “overwrite” the medallion helping it to rise visually. This small cross containing hexagonal motif is seen at the 5 o’clock position and is the only motif to actually “touch” the central medallion.

Part 3

A detailed analysis of a single not inscribed rug.

I am unaware of a single Lori Pambak rug, like the one pictured above, that’s inscribed with Armenian writing. I don’t think there are any known 18th century Dragon carpets inscribed with Armenian writing except the Gohar carpet dated to 1700. What purpose would an inscription have had on an expensive top quality workshop carpet unless it was a commissioned piece?

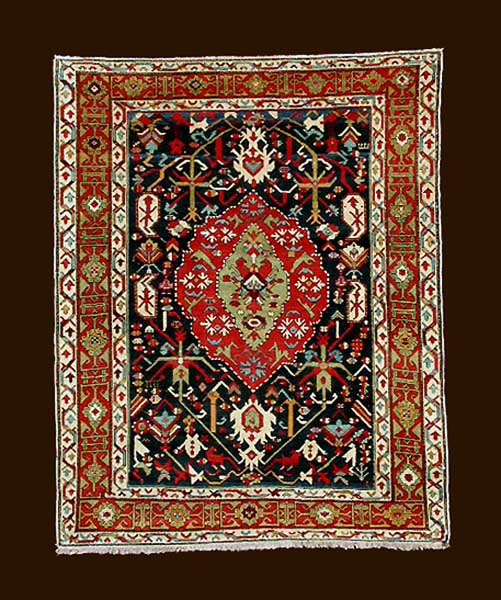

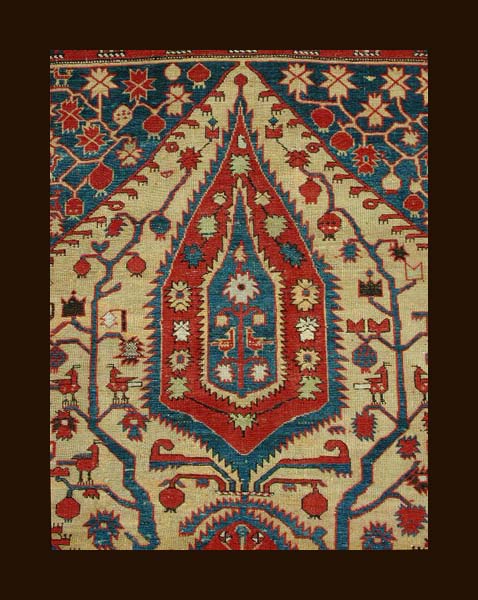

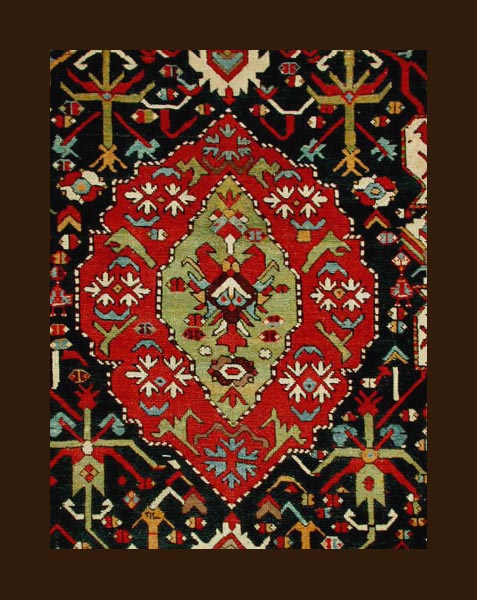

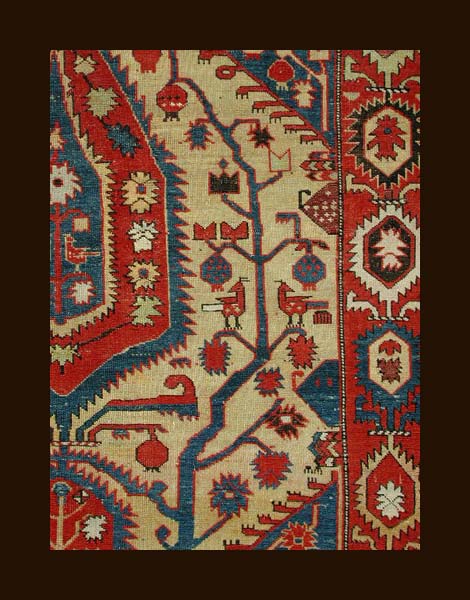

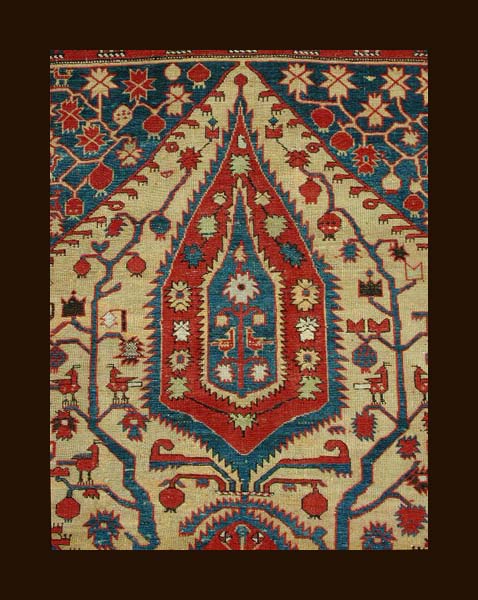

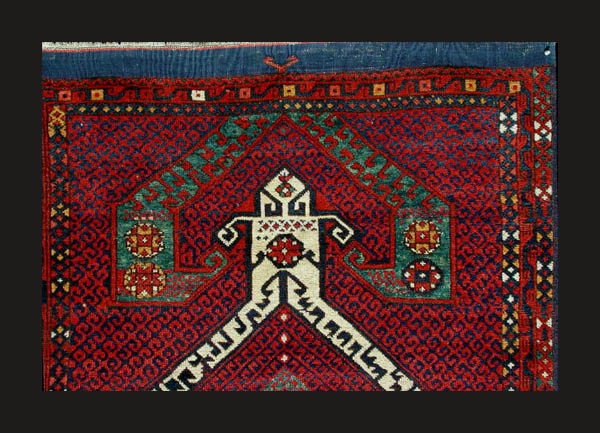

Look at this old Shirvan prayer rug. Lets consider the possibility that its weaver is Armenian. I will spend a lot of time (with some speculation) on this rug.

Less than ten such Shirvan ‘prayer’ rugs are known and all but one of them is published. Certainly a few more may come to light in the future. This ‘Shirvan’ prayer or wedding rug seems to have a Persian influence but some of the motifs are obviously derived from designs found carved on ancient Armenian churches. The low number of such specimens and their obvious “importance” suggests to me that these rugs were special dowry weavings. The one pictured above has iconography suggesting the details of two bloodlines. Such a weaving might be expected of a high class bride/princess for her groom/prince.

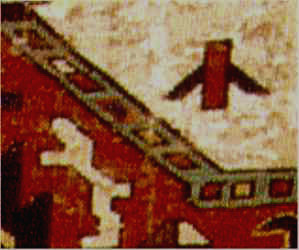

There are miniature crosses placed in a highly discrete yet restrained manner in this prayer rug. The bodies of four prominent birds sitting two each in the ‘family’ trees are decorated with miniature crosses as are a few of the pomegranates hanging from branches of the ‘family tree’ to the right. The highly specific use of tiny crosses in only certain motifs within this old Shirvan prayer rug suggests they may designate Armenian ancestry or even possibly ancestors.

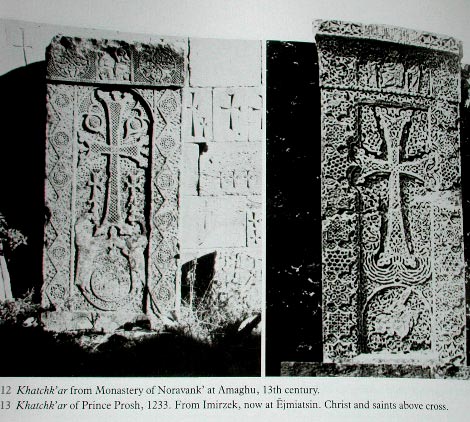

I found a possible inspiration for some of the motifs seen in this old Shirvan prayer rug in Lucy Der Manuelian’s preface to; WEAVERS MERCHANTS AND KINGS. There Dr. Manuelian gives a compilation of historically important Armenian predilections, trends, and inspirations for both illuminated manuscripts and carpets.

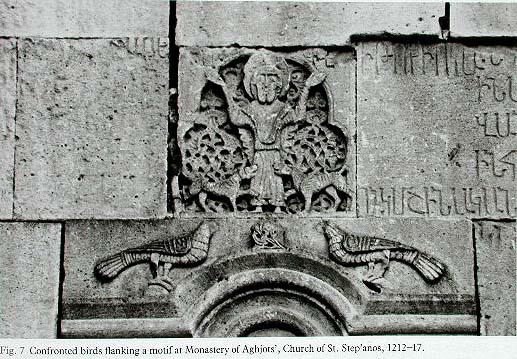

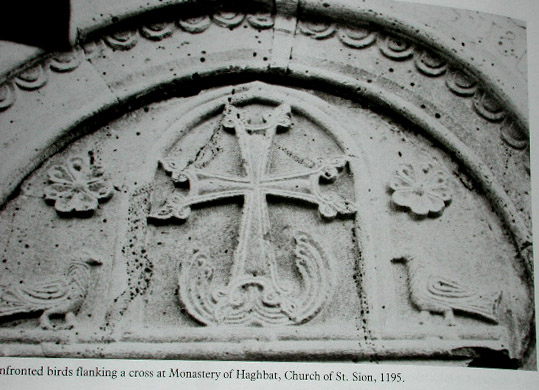

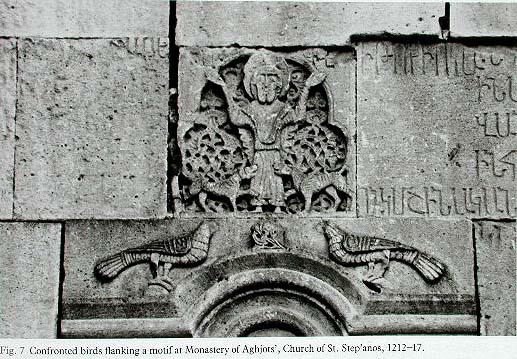

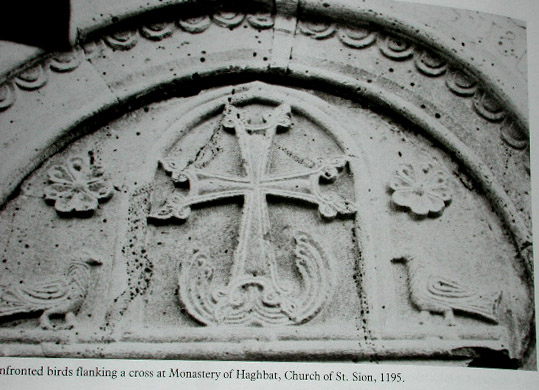

In figure #6 of her introduction to this book, Dr. Manuelian introduces a stone carving found within an old monastery arch that foreshadows the particular treatment of birds standing on the branches of this rug as well as the birds standing inside of its four corners.

After looking at this prayer rug for a long time I began to perceive a narrative relating to a love story embodied in its design. The individual elements of the love story are portrayed through a series of relational developments carried out between two ‘birds’.

The love birds are initially encountered in the two lower quadrants to each side of the central field, where each bird is looking backwards. I think it’s important to note that only the bird associated with the left side “sees” the other bird and consequently the boy sees the girl first and falls for her. Each bird, in its lone lower corner, has its own individualized samovar scattered amongst the many fruits and flowers of its quadrant.

In the lower portion of both upper quadrants one sees that the two birds are looking at each other across the field. Finally, in the upper portion of the left upper quadrant, the two love birds are portrayed kissing. This rug embodies the love story of two lovers plus their individual lineages.

Of stylistic note the inwardly facing aspect of each lower corner is decorated with many “feet” along with a scattering of pedunculated oval forms.

These elaborated invaginations help create a dimensional milieu; so that one perceives both ‘family’ trees as growing upwards into three dimensional space.

Here is my hypothetical analysis and opinion of this rug.

Look at the prominent and auspicious objects that hang from the branches of both trees in the field of this rug. On the tree to the left hangs a spotted (leopard) skin, an implement of war (resembling an English ball and chain), and a (Royal) Crown.

All three of these specific objects are associated with English nobility and by association with the Crusaders. One can hardly imagine a more noteworthy heritage for a Christian groom to have in early 19th century Armenia. Interestingly not one single pomegranate or other object besides the two prominent birds is decorated with any crosses on the left side. I interpret this to mean the groom was Christian but not necessarily Armenian.

On the tree to the right hangs a (Royal) Crown closely associated with a (Queens) white crown and both of these positioned above two smaller crowns.

The smaller red crowns might represent a prince or a princess. A few pomegranates hanging from the tree to the right are filled with tiny crosses. I wonder if the pomegranate fruits portrayed in this rug represent male ancestors. If so perhaps the many different colored sheep skins represent female ancestors. These trees may in fact define the actual family trees of an Armenian bride and groom. Both family trees terminate appropriately at the top of the field with crowns fit for a prince and a princess.

This rug embodies one of the clearest symbolic narratives I have ever seen woven into any Oriental rug. The only other rugs I am familiar with containing such symbolic familial information are very old Turkoman rugs.

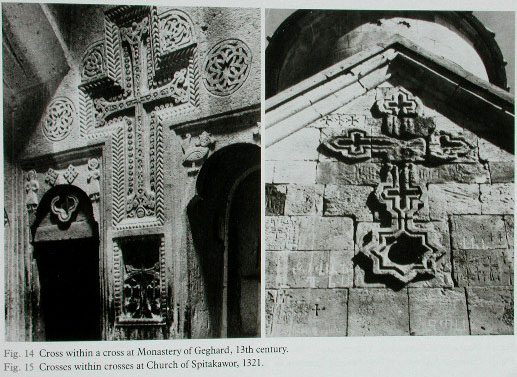

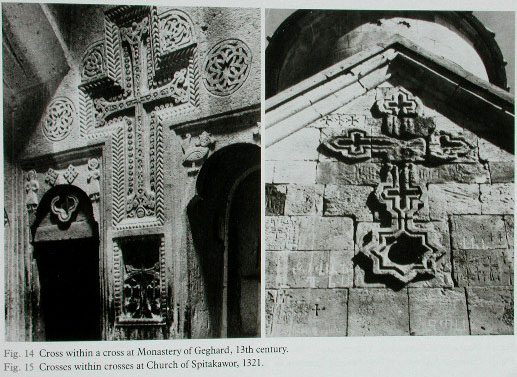

Much of the lower part of this old Shirvan prayer rug’s design can be related to aspects of figures seen published in Dr. Lucy Der Manuelian’s preface mentioned above. (slide of figure 7 WMK) In a prominent archway at the monastery of ‘Ashiots’, Church of St. Step’anos, 1212-1217, one sees birds in the superior quarters of the arch near St. Step’anos’s head. The outline of the fenestrated background upon which one sees St. Step’anos being flanked by two ‘deer’ with upraised legs is echoed in the general shape of the prayer rug’s field.

Further resonance is found between the rug and the archway in the particular stance and treatment of the two anxious ‘deer’ portrayed at the bottom of the rug and in the carving. Furthermore ‘subterranean’ branching forms, possibly representing the roots of the ‘family’ trees, seem to be firmly rooted in the blue waters of the church. (slide of the rugs bottom)

The image of St. Step’anos standing in the archway carving of the church is transformed by the weaver of the rug into a tree branching inside of a crenellated cartouche. The tree’s two lower branches hold shields surmounted by Christian crosses, much as seen laterally beside the Saint’s elbows in the church carving. In the church carving St. Step’anos’ arms are bent in a peculiar way and their exact shape is reproduced in the second set of branches exiting the central tree in the cartouche. Both of these arms are portrayed holding aloft an unblemished white sheep skin. The third set of arms doesn’t seem to hold anything but they are closely associated with two diamond star forms.

The top of the metaphorical tree in the rug’s cartouche represents St. Step’anos’ head. The rug’s central tree is elaborated at the top so it seems to be wearing a hat sporting an extension covering its ‘neck’, just as the ecclesiastical hat St. Step’nous is seen wearing in the ancient church carving covers his neck.

The “central mountain”, portrayed in the lower central region of this Shirvan prayer rug, is most probably a representation of the fenestrated background seen supporting the ecclesiastical and mythic figures carved inside of the archway at Haghbat monastery.

The triangles colored with a skew of hues that make up the “mountain” seen in the lower central portion of this rug resonates with the play of light and shadow one would have seen playing over the three dimensional surfaces of the fenestrated background of the church carving of St. Step’nous.

This Shirvan prayer rug was surely woven by an Armenian bride for her wedding and in its design she included information about the two families along with significant ecclesiastical symbols and designs. This weaving may be of historical significance to modern day Armenians seeking a window into their past.

I found Dr. Lucy Der Manuelain’s thoughtful and exhaustive writing concerning the historical inspiration for Armenian Church carvings, illuminated manuscripts, and carpets to be enlightening. I think her work sets the benchmark for future scholarship in this field.

Conclusion

This article will hopefully ignite another round of collegial debate amongst Armenian rug enthusiasts. Surely some imaginations will be stirred by my identification of this Shirvan prayer rug as an important Armenian wedding rug.

Jim Allen

connection obvious. The difference in the drawing of the cats’ shoulder silhouettes might indicate that the Mughal cat represented a running leopard while the Turkman example a galloping cheetah. The term for cheetah in Turkmen is “gechigaplan” (goat /tiger). The Turkman Khan’s were known to employ cheetah for hunting. I don’t think cheetah were ever native to Northern India but leopards certainly were.

connection obvious. The difference in the drawing of the cats’ shoulder silhouettes might indicate that the Mughal cat represented a running leopard while the Turkman example a galloping cheetah. The term for cheetah in Turkmen is “gechigaplan” (goat /tiger). The Turkman Khan’s were known to employ cheetah for hunting. I don’t think cheetah were ever native to Northern India but leopards certainly were.